Tags

dublin, France, gustave flaubert, ha'penny bridge, love locks, oscar wilde, Paris, pere lachaise, pont des arts, tourism, vandalism

At long last, the city authorities in Paris have announced that they are taking concrete steps to put an end to the ugly phenomenon of ‘love-locks’ that have blighted the city’s bridges and railings since the mid-2000s. Not wanting to seem overly harsh, the city has decided to encourage people to share ‘romantic’ photos of themselves on social media and to create what it has called a ‘social wall’. The urgency of dealing with the love-lock problem was starkly highlighted in June of this year, when a section of the nineteenth-century Pont des Arts – perhaps the structure most afflicted by love-locks – fell away after being damaged by the weight and corrosion from several hundred of these ‘romantic’ padlocks.

Locks on the Pont des Arts in Paris. By Disdero (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

I am unashamed to state outright that I despise love-locks. When I lived in Paris I tended to avoid the Pont des Arts, because it was simply too irritating to see couples adding their own padlock to the thousands that were already slowly corroding and damaging the structure of the bridge. Then the Pont de l’Archevêché, behind Notre-Dame, began to suffer. Then, when space on both of these bridges became tight, locks appeared on those typically Parisian railings in the vicinity of both bridges and beyond. If it’s a railing, and it’s near the Seine, you can bet there’s probably a rusty love-lock attached to it.

The phenomenon is not Parisian in origin, of course, and has spread beyond the City of Light. It has been suggested that it originated in Hungary, but it can now be seen in almost every city. In Dublin, people started to attach locks to the Ha’penny Bridge – though Dublin City Council have now announced plans to remove the locks once a fortnight. This may be a losing battle, however, as the Evening Herald has also reported that people are beginning to place love-locks on the newly opened Rosie Hackett Bridge. In Newcastle, the beautiful (and only recently restored) High Level Bridge, designed by railway pioneer Robert Stephenson, is also blighted by the phenomenon. A few months ago I was startled (and horrified) to see love-locks appearing on the ornate city crests on Sunderland’s Wearmouth Bridge. These disappeared as quickly as they’d arrived, however.

Perhaps I seem like a killjoy, miserably tutting at loved-up couples as I made my way around Paris. But to me, love-locks have always been a pox on the urban landscape, an unwanted and destructive intervention into a city. Everyone wants to leave some kind of mark, it seems – and this is the motivation behind the Paris city council’s attempt to get people to take selfies, accompanied by the hashtag ‘#lovewithoutlocks’.

For those who are part of the love-lock phenomenon, the idea of leaving a padlock (sometimes specially engraved with the lovers’ names; sometimes hastily scrawled with names in permanent marker) to rust away on a Parisian bridge while you get on with your life in New York or Shanghai or Rome or Ballyhaunis is a deeply romantic one. And leaving one’s mark on a monument or tourist attraction is nothing new. Think of the graffiti one sees scrawled into the stone walls of medieval castles by generation after generation of visitors. In 1851, during his visit to Egypt with his friend Maxime du Camp, the writer Gustave Flaubert was disgusted by the graffiti he found atop the Great Pyramid of Giza: ‘One is irritated by the number of imbeciles’ names written everywhere: on top of the Great Pyramid there is a certain Buffard, 79 Rue Saint-Martin, wallpaper manufacturer, in black letters; an English fan of [the soprano] Jenny Lind’s has written her name; there is also a pear, representing [French king] Louis-Philippe.’

I feel that Flaubert would have shared my irritation at the love-lock phenomenon. In spite of the ‘romance’ attached to them, they reveal a certain – albeit unwitting – disrespect for the city and its monuments, bridges, or basic street furniture. Whether they realise it or not, those who insist on attaching their clunky padlocks to the Pont des Arts see it not as a beautiful, functional structure in and of itself, which does not need embellishment by several thousand hunks of metal – but rather, as a structure that is there for their own use, intended to accommodate their personal romantic notions. What matter that the Pont des Arts or the Pont de l’Archevêché was there before they were, is used by thousands of other people, and will be there long after these tourists are gone? (Unless, of course, the bridges finally collapse under the weight of all those padlocks.)

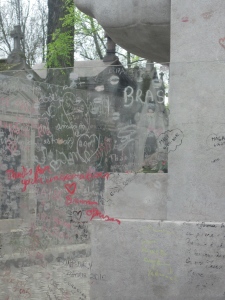

In Paris, examples of this rather self-centred approach to tourism exist beyond the love-locks. Oscar Wilde’s tomb in the cemetery of Père-Lachaise is a case in point. Wilde’s tomb is marked by a large limestone sculpture by Jacob Epstein, completed in 1914. At some point in the recent past – possibly in the 1990s, though the phenomenon intensified in the 2000s – visitors to Wilde’s grave began to plant kisses on it, thus leaving the sculpture coated in a greasy, smeared film of oil and pigment. The tomb was also marked with graffiti, ranging from the adulatory (‘We love you Oscar’, that kind of thing) to the downright bizarre (a heart-shaped potato, accompanied by the words ‘Jon Bon Jovi’ – see below).

In 2011 a glass barrier – part funded by the Irish state – was erected around the tomb, intended to protect the monument from further damage. It has not stopped the lipstick brigade, who have simply transferred their affections to the glass.

The persistent graffiti at Wilde’s tomb, like the love-lock phenomenon, seems indicative of an extremely individualistic attitude to tourism and to the urban environment. What matters is not appreciating the city for itself, or paying one’s respect to a writer by simply visiting his grave and taking a photo, but rather leaving a physical, literal mark – a rusty, corroding, greasy mark at that – on the urban environment. Such an attitude seems strange to me in a city like Paris, which is not exactly lacking in ‘romantic’ things to see and do that don’t compromise or damage the city. Unfortunately, I’m not sure how much this approach can be curbed. The expensive glass barrier has done little to spare Epstein’s sculpture from the kisses of Oscar Wilde’s devoted ‘fans’, and it remains to be seen how effective the city of Paris’s campaign for ‘love without locks’ will be.

Totally agree, except for the bit about Ballyhaunis. 😦